That Morimoto (or Otomo, as executive producer) wishes to plumb fiction for archetypes is not the issue. Eva, for example, is a prototypically sick, spurned woman, not only murdering her lover, but shacking up in a crumbling mansion to undo some prior hurt, a la Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham. This is because, for all of Magnetic Rose’s stylishness, the basics of ‘ what a good story is’ is never respected. Thus, we get three typical anime tropes right off the bat: steampunk, cyberpunk, and a re-iterated present, but without any deeper reason for these permutations, for the tale, as told, is banal, marred by poorly drawn-out characters, and leads to neither revelation, change, nor regress. The ‘Victorian’ world is not the world of the 1900s, yet Carlo (as well as others) are twentieth-century inventions, and opera festivals in Tokyo imply a diverse, modern world. It is also unclear what world Eva’s world refers to: there are references to Tokyo, for instance, but her own memories swirl into a rose-shaped cosmic graveyard that is clearly not Earth, with even contradictory referents in the memories, themselves.

#MEMORIES 1995 FULL#

Yet it also looks towards an equally anachronistic future, full of huge, junky spaceships, cigarettes, and a 1950s-style home Heintz’s family apparently lives in. It is, to be sure, an anachronistic setting: the ‘past’ is presented in Victorian, almost steampunk terms, replete with holograms, vast living spaces, decadence, robotic cherubim, and silly, exaggerated interactions. Magnetic Rose ends with Heintz floating in space amidst rose-petals, possibly dying, and possibly even accumulating, in Eva’s manner, his own memories, and waiting for the cycle to be broken by future explorers.

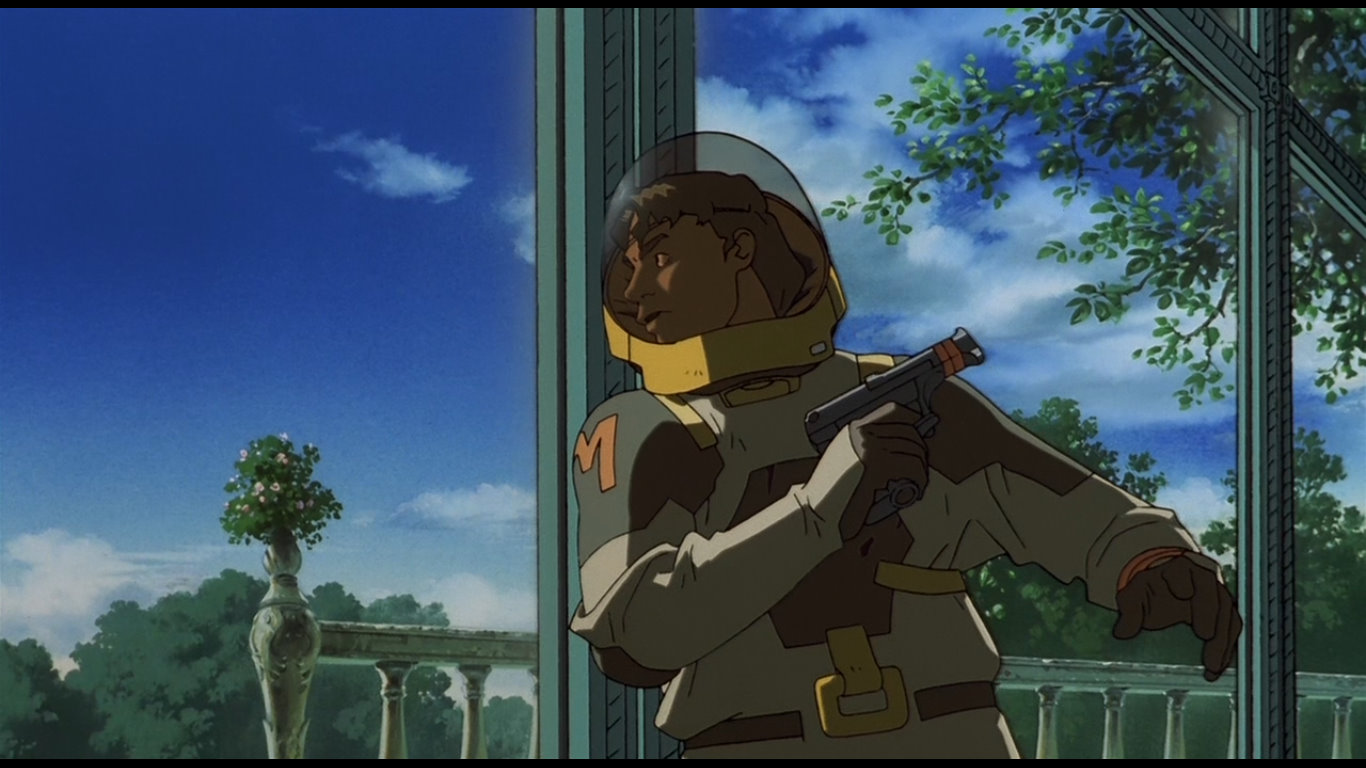

The hallucinations grow violent, culminating in the ‘death’ of Heintz as if he were Carlo, Miguel’s imagined fling with Eva, and Heintz’s own probe into his family, leaving the viewer unsure on the question of his daughter’s death. In time, however, another crew member radios from their spaceship, and informs them of what he’s found. At first, they do not realize who the owner of this place is, as Eva zips in and out of the landscape, inducing hallucinations that tangle up her own life with theirs. Once landed, the two enter a Victorian-style mansion propped up by holograms and ‘genuine fakes’ that, once discerned, crumble and disappear. They witness an SOS signal in deep space as Heintz and another crew member, Miguel, go on to investigate. The details are slowly discovered by a crew of scrap collectors, of whom Heintz, a father seemingly on leave from family life, is the mysterious protagonist.

They are happy, briefly, until Eva loses her voice, then Carlo, and ultimately murders her former love in order to trap him in a cycle of unchanging memories. Memories begins with Koji Morimoto’s Magnetic Rose, a highly stylized tale of an opera singer, Eva, and her chief fixation: her prior life with Carlo, a famous tenor with whom she went on to win world acclaim. Yet instead of positing an unpopular claim, first, and bracing for the fallout, I will present the evidence, bit by bit, precisely as the film presents it, so that the sum is unassailable, and that the work’s poetic status might get the treatment of a more mechanical eye. Is this an issue? Perhaps, but since it’s the least of the film’s faults, I do have an idea of what it all means, and why Otomo made these artistic decisions. In brief, whereas the title could be said to cohere too neatly with the work’s first forty minutes, the last eighty, well, cohere not at all, despite containing some of its best material. Yes, the word is uttered early on, and has an obvious, ham-fisted, 1:1 relationship to the first of the collection’s three anime shorts, but what about the rest? There is very little to say, really, since the others tackle different tropes, and have only a slipshod connection to one another in the fact that they’re the film versions of three of Otomo’s previously written stories. In reading the reviews of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories (1995), one might be particularly struck by what is not said: that, for all the ways that titles might recapitulate, refract, or even turn away from a film’s content, there is almost no discussion of what the title means to the work at hand. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories kicks off with Eva in Magnetic Rose.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)